2,000 stars. That’s the approximate number of stars you can see in Smith College’s night sky with your naked eye. Compared to the 6,000 stars that we used to see years ago, the loss is staggering. Over 60% decrease in the number of stars results from light pollution. Besides robbing the night sky of its natural beauty, light pollution may even affect your health.

Published in Science on January 19th, 2023, a multi-university research team reported a seven to ten percent increase in global sky brightness per year in the human visible bands. This rate of change corresponds to an increase in sky brightness by more than a factor of four in an 18-year period. For example, in a location with 250 visible stars, the number would reduce to 100 visible stars in this period.

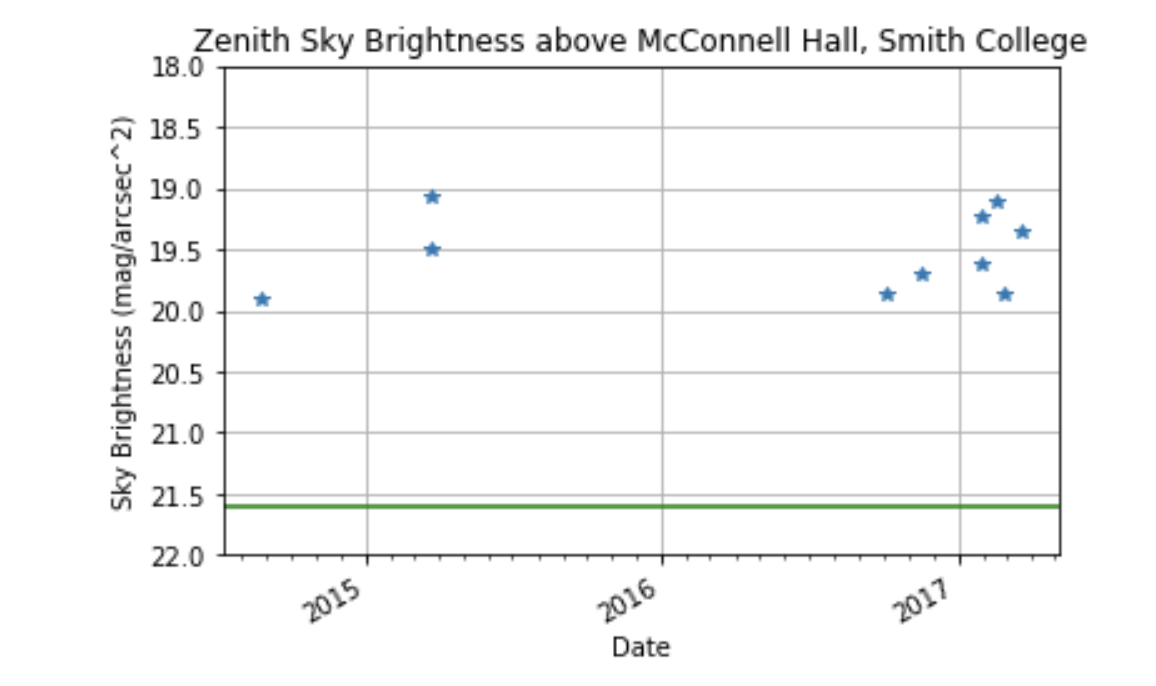

The sky above Smith College, too, has been affected by increasing light pollution. The night sky at Smith College is approximately six times brighter than the natural sky. Calculated using data obtained by students from McConnell Hall rooftop from 2014 to 2018, the darkest sky at Smith College was approximately 20 \(mag/arcsec^2\) (unit for sky brightness). In contrast, the value for the dark natural sky is 23 \(mag/arcsec^2\).

To understand the effects of light pollution at Smith College, we interviewed James D. Lowenthal, Maty Elizabeth Moses Professor of Astronomy. Professor Lowenthal, the Massachusetts chapter leader of the International Dark-Sky Association, studies galaxy formation and evolution.

“Everybody should see the milky way,” Lowenthal says. “It’s part of our natural home. Everybody deserves to see it.”

Light pollution means more than not seeing the milky way. Perhaps surprisingly, it strongly affects the health of humans. Nighttime exposure to artificial lighting influenced circadian rhythms, hormonal cancer, immune function, mood disorders, and risks for vector-borne diseases. A Chinese team, publishing in the November Diabetologia, even found that light pollution increases the risk of diabetes, with 9 billion cases of diabetes for those aged 18 or older in China attributed to exposure to artificial light at night.

At Smith, a campus-wide official policy responsible for outdoor lighting is yet to be mandated. “There are five very basic principles that I would love Smith to adopt officially,” Lowenthal said.

All lights should have a purpose. They should be targeted and controlled. Warm colors should be used whenever possible, and the brightness should be adjusted to the lowest level necessary.

For example, “the lights in Smith’s athletic field are terribly designed”, Lowenthal said, “and are scattered everywhere”. These lights should be replaced with better lighting directed downwards, invisible from the far side, and timed.

There are good lights and bad lights everywhere on the Smith campus. Over the years, professors and student groups from Astronomy, Biology, and Physics have worked with campus administration and facilities to improve lighting. Although some implementations and works have been done, they do not tend to last long or become official.

“That’s one thing that we should do,” Lowenthal said.